Whether you think of the Camino de Santiago as a spiritual journey, a challenging hike, a devotional pilgrimage, or simply a way to escape the grind of modern life—one of the most striking elements of the Jacobean Way is its abundance of ancient hermitages, chapels, churches, cathedrals, and abbeys. And while the cathedrals and abbeys might be the head-liners of the show with their awe-inspiring artwork and over-the-top architectural features, some of the lesser-known chapels and smaller churches harbour mysterious secrets and intriguing histories.

Santa María De Eunate

On the Camino Frances, between Pamplona and Puente-la-Reina, pilgrims have the option to follow a trail that leads to Santa María de Eunate, an ancient and enigmatic octagonal chapel.

This resolute stone structure seems to sit in the middle of nowhere. Sprouting from a vast, flat landscape, the striking chapel dominates the horizon, despite its relatively modest size. One of the finest, yet most puzzling, examples of Romanesque architecture on the Camino, Santa María Eunate is worth the extra walk.

Constructed as a slightly irregular octagon, Santa María Eunate is consecrated to the Virgin Mary. Built in dressed stone with a three-sided apse and alabaster windows, its ancient walls support a spectacular vault butressed by eight stone ribs. Similar, but not identical to the vault of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre of Torres del Río, which is located further along the Camino Frances, Eunate clearly reflects Muslim influences.

Outside, the octagonal chapel is encircled by a series of decorative arches. Contemporaneously documented by architect, José Yárnoz Larrosa, some of the chapel’s arches were restored and rebuilt in the 1940s, along with an archaeological deconstruction and restoration of the vaulted ceiling, roof, and bell wall to mitigate water leakage, trapped humidity, and weight issues that threatened to collapse the vault.

While little is known about the original purpose of the monument, locals still celebrate a traditional “romería” to Eunate, a mini pilgrimage of sorts, a procession that honors the Virgin of Eunate. This romeria is actually the oldest-known and the only documented purpose ascribed to the chapel, its identity as a site of Marian devotion being attested to as early as 1487. Beyond this romeria and the chapel’s dedication to the Virgin Mary, however, the original provenance of the chapel remains a mystery.

Situated in the Ilzarbe Valley in the municipality of Muruzábal, today the chapel is located at the geographical centre of Navarre. This has inspired some devotees to perpetuate the theory that Santa María de Eunate was intentionally constructed over a powerful convergence of telluric energies. However, at the time the structure was built, Navarre had very different borders, meaning the chapel was not at the centre of the region. Still, many pilgrims do feel a powerful energy and peace in and around the chapel.

Another theory attributes the chapel to the Knights Templar. With its distinct octagonal shape, which is a hallmark of Templar construction, this attribution seems plausible on the surface, but despite its location on one of the very pilgrimage routes that the Templars protected, there is no historical evidence for this assertion—no record of the land or the structure ever belonging to or being under the protection of the Order.

Others associate Santa María de Eunate with the stonemasons and craftspeople who carved the fanciful signs and iconography atop its columns and promenade. These believers look for initiatory symbols and esoteric messages among its stones. Still, there is no proof.

Another legend, which dates back to the 17th century, proposes that the structure was a funeral chapel for medieval pilgrims. Local tradition suggests it was built for a noble woman whose tomb is beneath the chapel. The likely source of this legend, a 17th-century document, claims that, ‘among other graves there is a very notable, major tomb in which the Queen or Lady who built … the church was buried, and each year they … commemorate her….’ But while Larrosa and his team did excavate human remains (see above) during the 1940s restoration, they did not locate the remains of a queen. Larrosa also points out that this story was written down 400+ years after the chapel was built.

While old traditions persist, new lore also emerges. Today, pilgrims who visit Eunate encounter a serenely silent monument whose stones speak only in images, textures, and symbols, sharing fragments of a largely forgotten story. Now cared for by a confraternity that maintains the site, Santa María de Eunate still hosts masses and events such as the annual romeria that venerates the Virgin de Eunate. Today pilgrims also believe that walking around the chapel’s arched cloister three times barefoot will help you find peace on your journey.

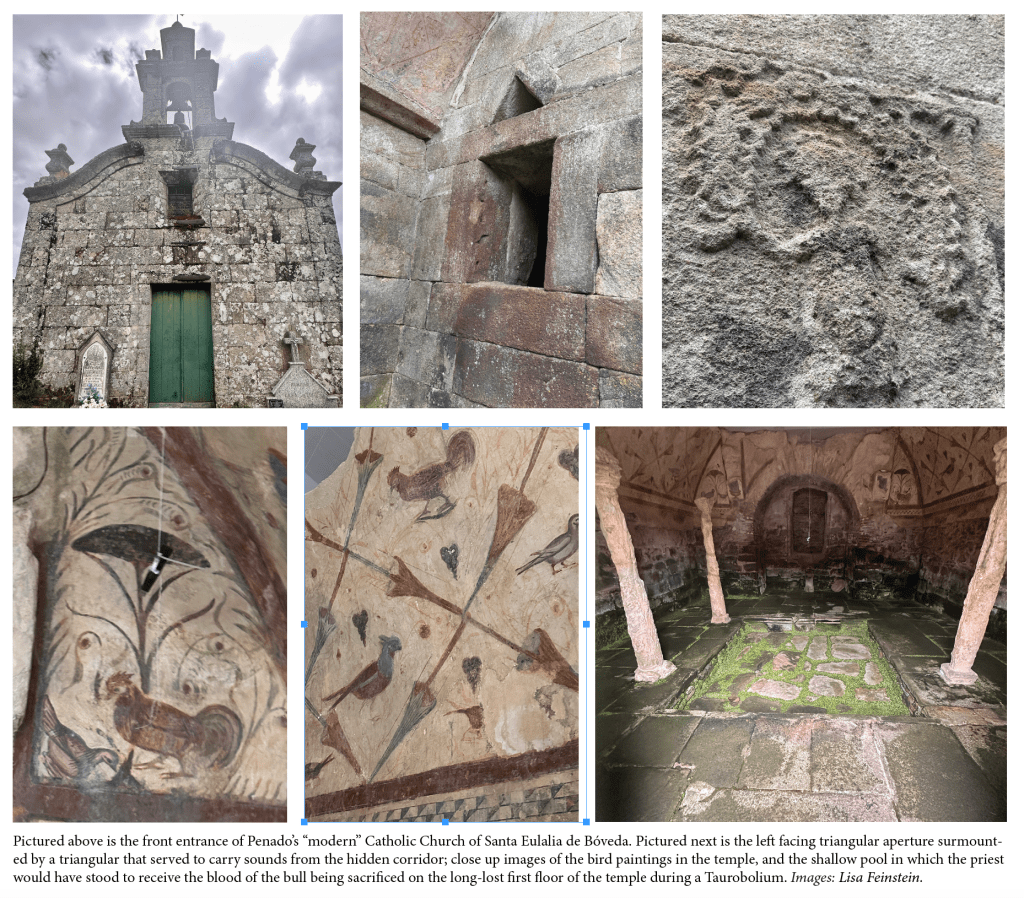

Santa Eulalia De Bóveda

Along the Camino Primitivo, about 14 kilometres from the Roman walls of Lugo, Santa Eulalia de Bóveda is another enigmatic church that stubbornly stands on a foundation of ancient mysteries. Literally.

Like a scene out of an Indiana Jones adventure, in 1914, a parish priest assigned to Santa Eulalia, José María Penado, discovered a secret passageway under the church’s cemetery. Once uncovered, the passage descended into a stony, underground crypt, a primeval pagan temple beneath Penado’s church that was dedicated to a mysterious cult where strange rituals and ancient blood sacrifices took center stage.

Delayed by scepticism, a lack of funding, and the timeless glory of bureaucracy, the first excavations of the site did not happen until 1926 and only ramped up in 1927 after a delegation of academics and government types gathered to assess the monument. Still, it wasn’t until 1931 that the chapel was officially designated a national historic monument.

Today, the subterranean temple’s impressive stone entrance can be accessed via flanking staircases, a literal descent into the depths of sacred Mother Earth. From those stairs, the ancient Roman exterior features a central entryway flanked by two small rectangular apertures surmounted by triangular openings.

After passing through the central entryway and a subsequent ante-chamber, the interior of the lower sanctum features a shallow pool, which was likely originally larger and would have been fed by a nearby running stream.

Around this ritual pool, the square floor plan of the sacred space measures 12 meters on each side, with two parallel perimeter walls running along three sides. The exterior perimeter wall functions like a retaining wall on those three sides, while a parallel interior wall, a foundation of sorts, along with the front entryway wall, bears the weight of the vault and, originally, the weight of the second floor.

Along the back wall of the temple and along the side walls, these parallel interior walls create a narrow, hidden corridor around the main interior space of the lower sanctum. Meanwhile, the small rectangular apertures surmounted by triangular openings that adorn the front entryway would have provided ventilation at either end of the u-shaped corridor. However, they also functioned as speakers, an amplification system, not unlike the small doors on the face of an early twentieth-century Victrola, serving as volume control.

But amplification for what?

The fantastic wall paintings inside the temple help to provide an answer to that question—and along with other carvings and images etched into the stone—help to identify this mysterious Roman temple as a sanctuary dedicated to the earth goddess Cybele and her consort, Attis.

Now suspended songless in time, 2,000 year ago the vibrant birds on the temple’s walls would have sang. Painted in an earthy palette of ambers, greens, and blues with detailed brush strokes, these peacocks, partridges, pheasants, and other game-birds cavort with hens, a goose, a duck, and other domesticated birds. But how did they sing? The answer lies in the secret corridors created by the double layered walls of the lower temple.

Scholars believe that the lower portion of the structure served as an oracular temple. The priest or oracle at the site would care for a number of birds kept within the thin corridor hidden along the perimeter. When offerings were made or questions were asked of the oracle, the birds could be enticed to sing. However, since the live birds were completely obscured from the view of the devotees, the sound echoing against the walls would create the aural illusion that the painted birds were miraculously singing, reinforcing the divine power of Cybele to speak through the oracle. In essence, the entire subterranean chamber functioned like a special effects machine, manifesting a mystical experience for worshipers. The corridor was likely also used to echo chants and invocations, not unlike the Great Oz’s voice booming from behind a velvet curtain.

(Schlunk, 1935) including a longitudinal section and the exterior elevation.

Another connection between the live birds, the painted birds, Cybele, and the history of this site can be found in the name that the Catholic Church transferred to the temple after banning the worship of Cybele—and re-branding the structure as a Christian house of worship.

The name Eulalia is derived from the Greek prefix, “eu-” which means beautiful, good, or enjoyable, as in “euphoria”; and “-lalia”, which is a form of the verb “to speak or voice”. So “Eulalia” literally means “beautifully voiced” as in a singing bird or the beautiful, convincing words of an oracle.

In the Catholic Church’s historiography of Saint Eulalia, at the moment of her martyrdom, a dove flies out of her mouth, and thus she was designated as the patron saint of birds. This is a convenient and clever tale that syncretizes and Christianizes the figure of Eulalia with that of Cybele, a beloved pagan goddess. Through this syncretization, a people who are hesitant, or even resistant to giving up their old gods in favor an unfamiliar deity, are presented with a middle ground—a new figure that retains the imagery, symbolism, and passion of their old god. In essence, the Church transforms Cybele into Eulalia, tears down her temple, and builds a Christian Church on top of it— physically and metaphorically. Brilliant.

And this pattern appears in other places. Eulalia is also the patron saint of Barcelona. And if you have ever been to her cathedral, you’ve likely seen the live geese and other birds still kept in Eulalia’s temple in Barcelona, to this day. Barcelona’s cathedral is quite literally a stone temple where the songs and calls of Cybele/Eulalia’s birds still echo and reverberate throughout the walls. Sounds familiar …

Back at Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, above the extant subterranean temple, the long-gone second floor of the original Roman structure was almost certainly designed to host not birds, but a devotional site to perform the Taurobolium, the ceremonial sacrifice of a bull.

“Deep down into the depths the priest descends, his head with elaborate ribbons bound and crowned with gold; his sacerdotal robe made of silk, and in old Roman style, tied tight round his waist…”

Thus the 4th century Roman poet, Prudentius, describes a priest descending into the lower level of Cybele’s temple prior to the performance of the Taurobolium. Once in the crypt and situated in the shallow pool of that lower sanctum, the priest can see light streaming through holes and slits above his head. And he must have heard the raging of the hooves and the pounding of the beast’s breath as the bull was led into the first-floor sacrificial area directly above him.

Prudentius goes on:

“The formidable bull with lowering brow, whose horns and withers are decked with garlands, is escorted to the spot; his forehead glitters with trembling gold and little golden discs flash on his flanks. The victim is thus rigged up to die and with the sacred spear they penetrate its chest…”

Below in the lower temple, the priest prepares:

“A stream of gushing blood pours … an all-pervading odor spoils the air. Through thousands of fissures. Now the shower drips sordid fluid down the dismal chasm and on his head, the priest catches the drops with utmost care, his vestment soiled with blood and all his body dabbled with the gore. Nay, bending back, he presents his face, his mouth, and cheeks now to the scarlet flood; his eyes he washes in the gory flow. He moistens then his palate and his tongue and sucks and sips and gulps the somber blood.

The bloodless rigid body of the beast is dragged away… and the priest, a gruesome sight, emerges from the chasm… polluted by his recent horrid bath he is respectfully, but from afar, saluted because the crowd has seen how, in his tomb, a bull’s blood has washed him clean.”

While many questions remain about the history of Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, Prudentius’ shocking words capture an emotion that is quite distinct from the tenor of today’s Camino. It is in this very distinction that the mystery of this incredible temple continues to fuel our wonder, our curiosity, and our imagination.