We all have secrets—and we all have stories. Usually we hide our secrets, rarely revealing them to even our closest friends or family, while our stories emerge from the experiences, memories, and inklings that we feel compelled to share. Yet somehow, my mother taught me that the boundaries separating our secrets from our stories can be slippery borders that migrate and vacillate, thin lines growing intermittently thicker—then whispery thin again—sometimes even disappearing.

My mom was a reticent storyteller—but a storyteller none the less.

Growing up, I treasured my mother’s stories about Loretto Niagara Academy, the all-girls boarding school in Canada where she spent several years of her life. She may have been there six years, eight years, or ten years. I’ll probably never know for sure. My mother was stingy with details and specifics—and she never told a story on demand. The time had to be right and there was no prodding her—so I never knew when she might delve into a memory about her mysterious childhood. And even though I loved to listen to her reminisce about her adventures in Niagara Falls, I was a skeptic, never exactly sure which of her stories were fact and which were fantasy.

But I also didn’t care.

I have vivid memories of my mother’s stories about hanging out of the windows of Loretto Academy, waving at the handsome young men who lived and studied across campus at the Carmelite Seminary, despite the fact they were training to become priests. She unabashedly bragged about the time she and her girlfriends hitchhiked to New York—the self-proclaimed prettiest of the bunch scooching up her dress, just a little bit, then thumbing down a car while the other girls hid in the bushes. When some poor schmuck pulled over to pick up what he assumed was one pretty girl, they all jumped out and loaded into the car.

When I was about eight years old, my mother told me that she had taken violin lessons at Loretto—and that her violin case had been confiscated at the Canadian border as she was heading home to Pennsylvania for summer break one year. From that moment on, I wanted to take violin lessons. So my mom arranged it. For more than ten years I played in youth orchestras, community symphonies, folk groups, school musicals, talent shows, and recitals at Eastman Theater. Every Saturday my dad took me to my violin lesson, but my mom never joined us. And she never picked up my violin to play. Not even a simple little song—no matter how much I begged her.

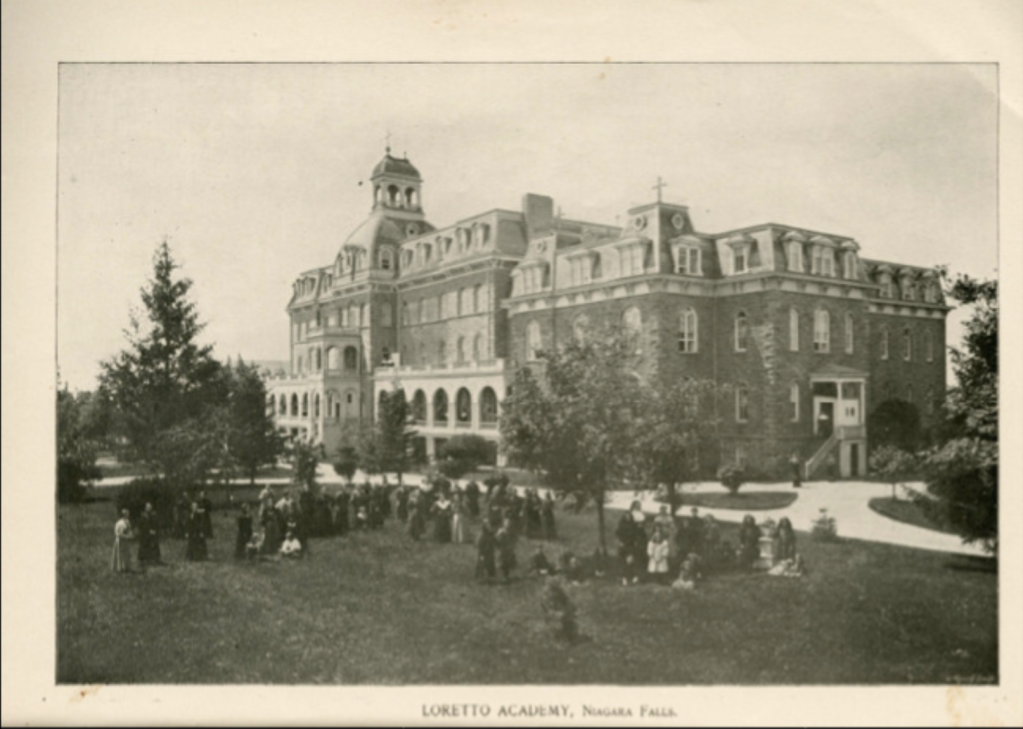

But I wanted to be like my mom—or at least how I imagined she must have been at my age. As a child, her life sounded like the behind-the-scenes stories that might have been edited out of my Madeline books. The boarding school, the uniforms, the adventures, the strict teachers—and even though my mother’s school was not an old house like Madeline’s, when we drove up to Niagara Falls, to me, Loretto Academy looked like a mansion.

In an old house in Niagara

That was covered in vines

Lived twelve little girls

In two straight lines.

In Ludwig Bemelmans’ books, Madeline was the smallest and bravest of the twelve girls. She was also the only redhead. My mom was a redhead too and her middle initial was “M”—which I imagined might have stood for Madeline. But my mother had always les me to believe that her middle name was Marie. It wasn’t until after her death that I learned her middle name was actually Magdalene—the original spelling of Madeline.

Even though Madeline lived in Paris, as a child I found ways to connect my mother’s Canadian adventures to the little red-haired girl. Like the 90-year-old nun who “taught” my mother French at Loretto. Each day, the old nun, in her full penguin-chic, black habit—not unlike the sisters who taught Madeline—would start the class with a prayer and demand “Les plumes!” After the girls dutifully got out their pens and prepared to take notes, the old nun would promptly fall asleep at her desk. My mom claimed that the only French phrase she learned at Loretto was “les plumes.” It wasn’t until I travelled to France a year after her death that I discovered the French word for a modern pen is actually “stylo.” But I still prefer “les plumes.” It’s much more intriguing to imagine my mother crafting her loopy, graceful cursive with a feathery plume dipped into an ink well. And who knows? Maybe the Sisters of Loretto were truly keeping it old school back in the 1940s.

My mother had many stories—and I like to think that I absorbed every detail she shared with me about life at Loretto. I knew that her best friend’s name was Yolanda, but everyone called her YoYo. I knew that in her senior year she had a room with a window ledge so wide she could sit on it and look out at the falls at night. I knew she worked in the kitchen to earn her room and board because she was taken in at Loretto as a needy case, unlike the mostly privileged and wealthy girls who teased her and called her kitchen-maid. I knew all of these things and tucked them away like treasures. But there was so much I didn’t know and I desperately wanted to fill in the blanks. I never knew my mother’s maiden name until I was an adult. I never knew her mother’s name. I never knew what town in Germany her father was from. These were her secrets.

I only have one photo of my mother in her school uniform. A print of that photo has been hanging in my kitchen since she died. It’s black and white and she looks small and stoic. She is standing on the massive stone steps that grace the front of Loretto Academy. The photo is grainy and old, but I can see myself in her blurry face. She looks like she’s about 12 years old, so I tell myself the photo was taken in 1946—shortly after World War II ended.

Growing up, I never knew my mom’s true age. My whole life I thought she was born in 1946—but there she is in that photo, standing on the steps of Loretto Niagara Academy in her thick black stockings, long blazer, and stiff woolen jumper. I never knew she lived through World War II. I never knew that I could have begged her to tell me stories about those years. What was it like to have German-speaking parents in the US at the height of World War II? Did she and her brothers gather around the radio to listen to the news overseas? Did some of the girls at school have brothers and fathers who were fighting?

A few years ago, a friend and I camped outside of Niagara Falls with plans to ride our bikes through the city. After riding to the falls, visiting the Nikola Tesla statue, and sneaking our phones through the broken glass windows of the old, abandoned hydro-electric stations to snap pics of the silent machinery still entombed inside, we rode our bikes to Loretto Academy. Even though it’s no longer a school, the building still stands, set back on a sprawling lawn on the banks of the Niagara River overlooking the falls. In fact, Loretto is situated on some of the most desirable real estate in Ontario. Over the years, developers have proposed projects that would attach high rise casinos, hotels, and shopping centers to the school—projects described as “historically sympathetic adaptive reuse.” But for now, it still stands alone, stubbornly similar to how it must have looked when my mom was there in the 1940s.

When we arrived at the Academy on our bikes there was nobody in sight, even though it was the middle of the day. I remember posing on the steps as my friend patiently gave direction and took photos while looking at the black and white image of my mother from 1946. I wanted to stand where she had stood. I wanted to look out at the falls and see what she had seen that day—just one year after World War II had ended. I wanted to think about her harsh, abusive German parents, still waging their own battles at her occupied home front in Pennsylvania. Hurled bottles, fiery words, and clenched fists taking the place of heavy cavalry and bombings. I hoped she felt safe being on the other side of the border—the swirling waters of the river and the thunderous falls separating her from the rage and chaos at home.

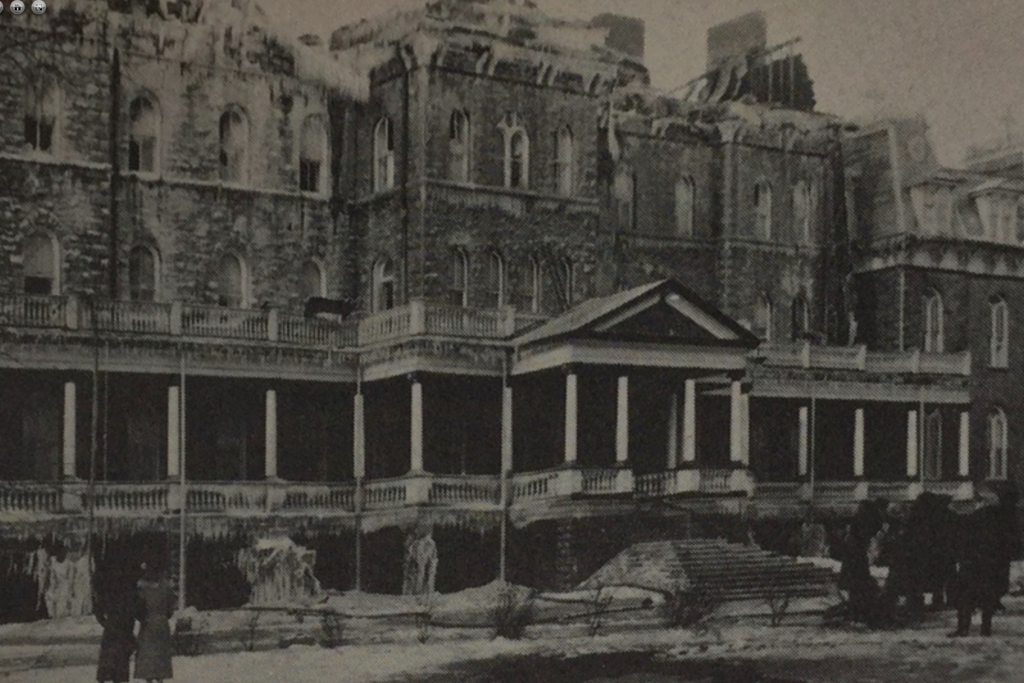

After we took what felt like a hundred photos, we stashed our bikes and walked around the outside of the school. It’s a gorgeous building. The Sisters of Loretto originally established the school in 1861 in an already old and dilapidated inn that was situated on what would become the Academy’s manicured front lawn. When the new school was finally completed in 1871, it consisted of classrooms, boarding rooms, a convent for the nuns, and a chapel. In 1890 and 1925 the school expanded even further into an architecturally stunning manse with a sprawling front porch, and three full stories topped by a Mansard roof. But in 1938, when my mom was barely four years old, and surely not at Loretto yet, a disastrous fire struck:

On January 10, 1938, the students had just returned from their Christmas vacation. They were getting ready to settle in for the night when a fire was discovered. The local fire departments as well as the Niagara Falls, New York fire department responded quickly, but there was a strong wind on that bitter January night and the south wing was aflame in a matter of minutes.

I remember my mom telling me about that fire. The entire top floor with the gorgeous Mansard roof and a stunning upper cupola were destroyed and never replaced, but I learned those details on my own. The story my mom told was about a sacred statue that had stood above the rotunda over the front entrance. On that night in 1938, even though everything around that statue burned, the effigy itself went unscathed. It didn’t fall or crack from the scorching heat. It wasn’t even marred by ash or smoke. It emerged from the inferno in pristine condition.

In my memory, my mother told me that it had been a statue of St. Michael. I always imagined him brandishing ethereal wings and a gleaming sword, waging holy war against the devil as flames rose around the nuns, the young girls, and the school. Despite the blaze being so intense that it could be seen clear across the river—no lives were lost that night. In fact, there weren’t even any injuries. All the nuns and all 65 students walked out of the school unscathed, in my mind, thanks to the glory of St. Michael.

After my mom died, I learned that her story about the statue was indeed true, but it had actually been a statue of St. Joseph, not St. Michael. I’ll never know if my mom changed the story, remembered it wrong, or if I transformed dowdy old St. Joseph into battle-ready St. Michael. But in the end, the re-casting made for a better story. A vengeful angel with a fiery sword always trumps a sandal-clad, step-dad, carpenter. Sorry Joseph. Ultimately though, that’s how stories work. They evolve and change. They step away from their original teller, taking on a life of their own each time they are re-told. My mom shared many stories—and I am quite sure that my imaginative, childish mind changed more than St. Joseph.

And perhaps that’s because my mother also kept a lot of secrets. Secrets about her family and her life before she met my dad. As a child I was intrigued by the tiny breadcrumbs she sometimes dropped about her other life in Pennsylvania. And the bevy of aunts, uncles, and cousins whom I would never meet. So I pieced together those scattered tidbits throughout the years, blending them into something not unlike a mythos. In the story of my mother’s life, it was easy to fill in the holes and the gaps with stock characters and classical tropes that I had encountered in books.

In my mind, my mother’s brothers were Dickensian ne’er do wells—hard-baked street scoundrels pinching pennies and hawking stolen newspapers—but really just looking for safety and warmth. Even though he was actually a Bavarian railroad man, I conjured up images of her father as a dusty Steinbeck protagonist, struggling to get by, raising rabbits for food in the backyard. But he was belittled and bowled over by his harsh Teutonic wife, who was no less than a witch from a Grimm’s fairytale. I pictured my mother’s mother in all black with a severe bun of grey hair pulling tight on her wrinkled Aryan face, her Gypsy lips barking out invectives and insults in German. She beat my mother and her brothers so harshly that they were removed from their home.

When my mother told me that her father had hung himself in their garage—and that she was the one who found him I was appalled, but also morbidly enthralled. These things didn’t happen in real life. My friends had grandmothers who took them on vacation and bought them presents, nothing even close to a nameless Gypsy witch who cursed in German, beat her children, cast the evil eye on her neighbors, and drove her husband to wrap a noose around his neck and toss it over a beam in their garage. That was the plot of a movie or a play. Other families didn’t live like that. Or die like that. And I really wasn’t sure if the story about my mother’s father’s death was true or a dramatic tale. When I finally managed to locate his death certificate a few years after my mom died, I discovered that the story was indeed true.

Much like my mom’s stories about her Uncle Mike. Uncle Mike made moonshine in his bathtub. He gambled, he partied, and he loved to drive fast. One night, according to my mom, Uncle Mike got so drunk that he drove home from a hootenanny (definitely my word—not hers) and his wife fell out of the car. She just fell out. Oops. And Uncle Mike drove all the way home, not even noticing that Annie was missing—or that his car door was apparently wide open. That was another story I didn’t quite believe, until I unearthed a series of newspaper articles about Uncle Mike. The way the reporters and court records described it, the cops showed up at Uncle Mike’s door the next morning and charged him with man slaughter. So it was a story, but it was also true—yet tinged with a dark secret that my mom was never quite ready to share. But that was my mom. And I suppose they were my Uncle Mike and my Aunt Annie … but we won’t go there.

I know—and on some level I also understood as a child—that my mom lived a difficult, abusive, and sad life. But when she told her stories, I didn’t feel sorry for her. And most of the time she didn’t frame her stories as sad. Hard-knock, challenging, tough-nosed, and full of adversity? Sure. But not usually sad. So I saw her life as an adventure—even the parts that would never, ever, ever find their way into a Madeline book.

Many years later as an adult, watching my mom decline at the end of her life, I thought about how her stories had been tainted by strife and violence, but she had chosen to share them as anecdotal adventures, often leaving the tragedy of it all to linger in dark corners as secrets. In those final years, I think those secrets were pushing harder and harder to creep to the surface. My mother was scared and regretful. She worried that she had never accomplished anything. She worried that she had made horrible mistakes. And I think she worried that we would find out about her secrets and never forgive her for not sharing them—because in the end, it’s easy to see unshared secrets as lies. And even though she never said it, I know she was terrified that her secrets and her scars had kept her from living her fullest life—and had closed many doors for her.

When my friend and I were walking around Loretto Academy that weekend, there were many closed doors. And even if there had been an open, unlocked door, we certainly wouldn’t have let ourselves in. That would be trespassing. And illegal. But if we had been bold enough to open and step through an unlocked door, I would have walked that building’s hallways for hours, respectfully exploring every inch of the place.

I would have started in the basement, gawking at the industrial-sized washing machinery from the early 1900s that must have laundered hundreds of sheets, habits, and linens each week. I would have gingerly made my way up the grand staircase of the two-story entryway—above which St.Michael would have stood (or St.Joseph in the boring version of this story). I would have taken photos of the arched doorways with articulated transoms, the vibrant stained glass, the giant “Auspice Maria” monograph placed in an exquisite tile flooring, and a gloriously oversized painting of a majestic stag standing next to a statue of the Virgin Mary.

I would have had my friend take photos of me in the immaculate old classrooms with their early-1900s green and black chalkboards—thick dust coating their well-worn wooden ledges. We would have opened every cabinet in the antique science labs—disturbing nothing—but absorbing it all. We would have admired the abandoned swimming pool with its still intact locker room boasting a sign advising would-be swimmers that, “A cleansing shower must be taken before entering and re-entering the pool,” “SOAP & RINSE” written in all-cap red letters below, with a genial “thank you” added in script as an afterthought. And I would have quietly thought to myself, “I wonder if my mom read that sign in 1946?” while muttering out loud to my friend, “I can’t imagine my mother in a bathing suit!”

If there had been an unlocked door that I was brave enough to walk through that day, I might have discovered the school’s two-story gymnasium with gleaming hardwood floors and a performance stage at one end, where in 1947, the girls of Loretto Niagara Academy staged a production of The Maid of Orleans. And I might have imagined that my mother starred as Joan of Arc.

We also might have found the stunning old ballroom where I could have belted out a song, letting the walls of the wood-paneled room echo my own words back to me as I danced in silly circles, arms outstretched—my friend laughing and recording a video. And after exploring the nuns’ quarters, the bishop’s quarters, the Abbey room, and the chapel—I might have been drawn to the far eastern wing of the students’ quarters, to an empty room at the end of a hallway. A room dominated by a large window overlooking the river, with a ledge just wide enough for me to sit in, my legs slightly folded, as I gazed out at the falls glittering in a brilliant sunset—just like my mom might have done many decades ago.

That would have been a beautiful day and a great story, but a story that could never be shared. It would have to remain a secret, because trespassing, breaking and entering, and absconding with a dusty bottle of very old cheap champagne that had been sitting in an old kitchen for decades? Those are all crimes. So instead of opening that door, we got back on our bikes, rode up the hill to our campsite, and built a fire—most certainly not pouring two cups of cheap champagne into paper cups.

But … if we did have a dusty old bottle of champagne, we surely would have popped the cork as we watched the moon rise over Niagara Falls that night. And we would have made a toast to my mom. To her stories. But I also like to think that perhaps, we might have raised our glasses to the realization that sometimes, the only act more generous and kind than keeping a loved one’s secrets—is finding the right time to share them.

What an engaging and well told story!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I went to Loretto in the mid 70’s and absolutely Loved it and the friends I made including many of the Sisters.

This story brought me down memory lane and I was cheering at the end to what might have happened 😉

What a beautiful story.

Thank you!,

LikeLiked by 1 person